Columbia University

Irving Medical Center

Neurological Institute

710 West 168th Street, 3rd floor

(212) 305-1818

News

2025 - present | 2023 - 2011

August 6, 2025

By Lisa O’Mary

Caghan Kizil, PhD, MSc, Associate Professor of Neurological Sciences, comments on compelling results of a recent study that used an artificial intelligence (AI) method to develop a precision-focused treatment for patients with Alzheimer’s disease. “This good example sets the standard for next studies about how computational biology, big data, clinical data, translational neuroscience, and animal models can come in to create faster or smarter therapeutics,” Dr. Kizil said.

[read more]

Source: Medscape

July 28, 2025

By Linda Carroll

Adam M. Brickman, PhD, Professor of Neuropsychology, talks about the importance of physical activity in keeping our brains cognitively healthy. Two recent studies showed that walking and a healthy lifestyle may benefit significantly, especially those who have an APOE4 gene mutation and are at a greater risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease.

“Sometimes initiating new healthy behaviors is difficult for people," Dr. Brickman said. "Knowledge of being at increased risk for Alzheimer’s disease by virtue of having an APOE4 allele(link is external and opens in a new window) may help inspire or motivate lifestyle changes to mitigate that risk.” [read more]

Source: NBC News Online

July 29, 2025

Davangere P. Devanand, MD, professor of psychiatry and neurology and director of geriatric psychiatry, led a study at Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons that aimed to examine the connection between Alzheimer’s disease and antiviral medication such as valacyclovir. Previous studies have shown that there may be a possible link between treatment for herpes infection and decreased likelihood of developing Alzheimer’s. “Based on those previous studies, there was hope that valacyclovir could have an effect,” said Dr. Devanand. “But no one had conducted a clinical trial to test the idea.” [read more]

Source: CUIMC Newsroom

June 25, 2025

By David J. Craig

James M. Noble, MD, MS, Professor of Neurology at Columbia University, is helping Maryam Zolnoori, a data scientist and assistant professor of health-sciences research at the Columbia School of Nursing, prepare a clinical study that will use new AI-based technology to screen people who may be at risk of developing dementia later in life. “The reality is that most cognitive assessments don’t happen unless a patient or family member raises concerns, and that often doesn’t happen in the beginning,” says Dr. Noble. “If you could identify people who ought to be tested just by listening to them talk during a checkup, that would obviously make a big difference.” [read more]

Source: Columbia Magazine

June 25, 2025

By Mohana Ravindranath

James M. Noble, MD, MS, Professor of Neurology at Columbia University and the author of Navigating Life With Dementia, described the difficulties that families face when their loved one is diagnosed with a cognitive disorder and shares strategies on how to better adjust. Families try to correct, rationalize, or reason with a family member who has dementia with the best intentions of attempting to recover their cognitive abilities, but it usually does not produce the desired effect. Dr. Noble says that “Not only does it not work, but it often backfires,” Dr. Noble said: Arguing or getting frustrated with a dementia patient can make them anxious or agitated, which can hasten decline and make caregiving more difficult. [read more]

Source: The New York Times Note: Accessing this article requires The New York Times subscription

June 3, 2025

By Linda Carroll

Yian Gu, MD, MS, PhD, associate professor of neurological sciences at Columbia University, described the MIND diet, which, in the most recent long-term study, showed how it may decrease the likelihood of developing Alzheimer’s disease and other forms of dementia later in life in those who follow it. “In general, the MIND diet is in line with the principles of the two diets it’s built from, said Dr. Gu. “Each of those diets has unique characteristics.” [read more]

Source: NBC News Online

May 25, 2025

By Mill Etienne

James Noble, MD, MS, Professor of Neurology at Columbia University and author of Navigating Life With Dementia, was invited by the writer of the article Dr. Mill Etienne, former resident and epilepsy fellow of the Department of Neurology at Columbia, to speak about the FDA’s recent approval of using Lumipulse blood test to diagnose Alzheimer’s disease. Lumipulse blood test is for the early detection of Alzheimer’s in those older adults who show signs of memory loss. It is not recommended for those who are asymptomatic. “Given that there is no specific treatment indicated for asymptomatic persons, there is a risk of introducing psychological harm at this stage,” explains Dr. James Noble. “Healthy approaches to lifestyle will remain central in adulthood whether or not someone has a positive test, and that advice will not really change. [read more]

Source: Forbes

April 25, 2025

Columbia Neuropsychologist, Miguel Arce Rentería, PhD, whose research focuses on studying aging and factors that impact Alzheimer’s and other cognitive diseases in the Latinx population, is interviewed by the CUIMC’s Health Insights about the physical and intellectual health benefits of activities such as pickleball. Dr. Arce Rentería describes pickleball's cardiovascular benefits, reduction in sedentary time, social engagement, and its positive contribution to brain health in the aging population. “For me, healthy aging means living independently, both physically and intellectually, for as long as possible,” said Dr. Arce Rentería. [read more]

Source: CUIMC Health Insights

March 25, 2025

Host Dr. Sperling and interviewer Grace Goodwin, in their Meet the Authors Podcast, produced by the Society for Clinical Neuropsychology discuss with Miguel Arce Rentería, PhD, Columbia Neuropsychologist, findings from the study that he led on the impact of multilingualism on cognition later in life. Participants in this study were from a wide spectrum of socioeconomic and educational backgrounds across India. The results vary between the groups that have formal education and those without. Similarities between the languages individuals knew were also a factor. This research provides a better understanding of how knowing multiple languages may strengthen cognition in aging. [listen to the podcast]

Source: Spotify

December 18, 2024

Columbia’s neuropsychologist Jennifer Manly, PhD, and neurology research scientist Justina Avila-Rieger, PhD, discuss the study they recently conducted looking at 21,000 people in the Washington Heights-Inwood Columbia Aging Project and the Health and Retirement Study. The results showed the link between later-in-life memory decline and sexism, especially among Black women. “It is likely that, for women racialized as Black, the intersectional impact of sexism and racism creates a unique form of oppression that has greater salience for cognitive health than sexism or racism alone,” commented Dr. Manly.

Dr. Avila-Rieger’s research concentrated on sex, gender, racial, and ethnic disparities in Alzheimer’s disease. “Alzheimer’s is a huge societal problem, particularly among women, who account for two-thirds of Americans with the disease. It’s imperative that we gain a better understanding of what is causing this discrepancy and what can be done about it,” said Dr. Avila-Rieger. [read more]

Source: CUIMC Newsroom

November 1, 2024

By Linda Carroll and Mustafa Fattah

Columbia Neurologist Lawrence Honig, MD, PhD, commented on a recent single-center study that used a transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) device to target the key brain network that stores memories and is typically hit by Alzheimer’s Disease. This study is at an early stage. “The findings are very, very preliminary” said Dr. Honig “On the face of it, if you look at the numbers, it did better on a number of scales compared to the sham treatment — that’s good. But as in any study, the devil is in the details.” Dr, Honig noted that this is a small, single center study, and that “a multicenter trial would offer a little more hope of generalizability.” [read more]

Source: NBC News Online

October 29, 2024

Columbia Alzheimer's Specialist Lawrence S. Honig, MD, PhD speaks about the people who have received the new monoclonal antibody Alzheimer’s drugs as a third member of this family of drugs, donanemab, has become approved. Dr. Honig, like many neurologists, notes that these drugs clearly have clinical efficacy at slowing disease, but that there are uncertainties over the risks versus benefits and important details such as duration of treatment. While uncommon, there have been some deaths due to the side-effects of these drugs, including one person at Columbia who developed the brain swelling known as amyloid-related imaging abnormality (ARIA). [read more]

Source: Science

October 21, 2024

Davangere P. Devanand, MD, Professor of Psychiatry and Director of Geriatric Psychiatry at Columbia, and colleagues conducted a new study that used impairment in an odor identification test and global cognition to predict cognitive decline and dementia. "Our study highlights a practical and cost-effective approach for predicting cognitive decline and dementia, which could greatly improve access to early diagnosis," said Dr. Devanand. [read more]

Source: HealthDay News

October 18, 2024

Columbia Neurologist Philip L. De Jager, MD, PhD and Neuroscientist Vilas Menon, PhD led a technically complex and innovative study of Alzheimer’s Disease that, according to Dr. De Jager, “highlights that Alzheimer’s is a disease of many cells and their interactions, not just a single type of dysfunctional cell. We may need to modify cellular communities to preserve cognitive function, and our study reveals points along the sequence of events leading to Alzheimer’s where we may be able to intervene,” explains De Jager.

[read more]

Source: CUIMC Newsroom

August 30, 2024

A recent study led by Columbia Neurological Scientist Caghan Kizil, PhD showed how the ABCA7 gene, prevalent among Black Americans, leads to an increased risk of Alzheimer's disease. “Our findings not only enhance our understanding of Alzheimer’s, but they also provide a new direction for developing treatments that could halt or reverse the progression of the disease,” commented Dr. Kizil.

[read more]

Source: CUIMC Newsroom

Jul 7, 2024

Dr. Miguel Arce RenterĂa, a neuropsychologist at Columbia University, comments that treatment that focuses on social issues may hold off the worst of Alzheimer’s Disease for years.

[read more]

Source: The New York Times

Note: Accessing this article requires The New York Times subscription.

The European Medial Journal interviewed Yaakov Stern, PhD, Florence Irving Professor of Neuropsychology at Columbia University Irving Medical Center about his early career interests and the journey that led him to focus on conducting research on cognition and aging. Dr. Stern discusses the history of Alzheimer's disease research and how it has developed over the course of his career. The interview further offers current takeaways from his research, and what needs, challenges, and personal goals Dr. Stern aims to achieve in his work [read the interview]

Source: European Medial Journal

April 24, 2024

The CUIMC Healthy Aging Initiative (CHAI), with the support of the Four Deans Fund and the Robert N. Butler Columbia Aging Center, organized the Healthspan Extension Summit that focused on the rapidly growing aging population around the globe and the challenges that long lifespan presents. Researchers across various disciplines at CUIMC presented their ideas on what can be done to insure healthy quality of life for the aging world’s population.

Adam Brickman, PhD, Jennifer Manly, PhD, Scott Small, MD, from the Department of Neurology, presented their research findings and led panel discussions on age-related illness. [read more]

The APOEε4 gene variant is a major genetic risk factor for developing Alzheimer's disease (AD) later in life. People with two copies of this variant are almost certain to develop the disease, yet some people with this variant do not get dementia and scientists are still figuring out why. In a recent study, a team of investigators led by Drs. Badri Vardarajan, Caghan Kizil, and Richard Mayeux analyzed the genetic data of 3,500 individuals from over 700 families of different ethnic backgrounds. Their findings, published in Acta Neuropathologica and highlighted in the CUIMC Newsroom, revealed 510 genetic variants that might protect against AD. These protective variants mainly affect the genes involved with the brain's blood barrier system. Notably, one specific variant in the fibronectin (FN1) gene stood out. Research involving over 11,000 participants from Columbia, Stanford, and Washington universities showed that this FN1 variant can reduce the risk of AD by 71% and delay its onset by about four years. It does this by reducing the buildup of certain proteins and inflammation in the brain's blood vessels. Experiments with zebrafish and human brain studies after death showed that losing FN1 function helps clear harmful amyloid proteins and improves the activity of immune cells in the brain. This groundbreaking research opens up new possibilities for treating Alzheimer's disease by targeting the brain's blood vessels.

Associate Research Scientist Sharon Sanz Simon, PhD was interviewed for the Alzheimer's Association inaugural ISTAART Voices global podcasts about her work with Brazilian immigrants. Dr. Sanz Simon talked about the challenges this community faces, and discussed the need for more research on Alzheimer's disease and related dementias in this underrepresented population. One of the goals of her research is to develop more culturally sensitive intervention strategies for aging and dementia prevention in the Brazilian community living in the US. [listen to the podcast]

Rafael A. Lantigua, MD, Professor of Medicine and Dean's Special Advisor for Community Health Affairs at Columbia University Irving Medical Center, received the Presidential Volunteer Award from New York State Senator Luis SepĂşlveda. Dr. Lantigua was also honored with resolutions enacted in the New York State Senate and Assembly, which celebrated Dr. Lantigua's significant impact. [read more]

Source: CUIMC Newsroom

April 14, 2024

A healthier diet is associated with a reduced dementia risk and slower pace of aging, according to a new study at Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health and The Robert Butler Columbia Aging Center. The findings show that a diet-dementia association was at least partially facilitated by multi-system processes of aging. While literature had suggested that people who followed a healthy diet experienced a slowdown in the processes of biological aging and were less likely to develop dementia, until now the biological mechanism of this protection was not well understood. The results are published in the Annals of Neurology.

“We have some strong evidence that a healthy diet can protect against dementia,” said Yian Gu, PhD, associate professor of Neurological Sciences at Columbia Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons and head of the Mailman School Neuroepidemiology Unit, and the other senior author of the study, “But the mechanism of this protection is not well understood.” Past research linked both diet and dementia risk to an accelerated pace of biological aging. [read more]

Source: CUIMC Newsroom

February 7, 2024

Associate Professor of Neurology James Noble, MD, MS, along with nine other faculty members from Columbia University Irving Medical Center, was recently inducted into the Academy of Community and Public Service (ACPS) in recognition of his exceptional efforts to promote health, well-being, and overall quality of life in the local communities of upper Manhattan, as well as nationally and globally.

At the event, Professor of Neurology and Vice Dean of Community Health Dr. Olajide Williams, a co-chair of ACPS, said of the awardees, “The work and dedication to community and public service of the people here today are nothing short of inspiring. I’m a big believer in inspiration, because inspiration is what sparks imagination, and imagination sparks innovation. And it’s innovation that is truly going to move us to a place where we can finally say, ‘out of many, we are one.’” [read more]

Source: CUIMC Newsroom

February 7, 2024

5 Questions With Dr. James Noble

Dr. James Noble isn’t one for being boxed in. The neurologist and neuroepidemiologist at NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia is an expert in dementia, but a sampling of his work reflects his broad clinical and research interests: He’s investigating the link between periodontal disease and Alzheimer’s disease. He’s developed a prototype for a device that helps diagnose concussions in real time. He’s researching how hip-hop can be used in health education and cofounded a nonprofit, Arts & Minds, to support the power of visual arts in improving wellness for dementia patients and caretakers.

These seemingly disparate projects all tie together for Dr. Noble. “First, I’m passionate about each of them. They tend to reflect a problem that I’m trying to solve or a question that I’m trying to answer,” he says. “And second, if I can prove in a methodical and scientifically rigorous way that all these things can make a difference for people, I believe they are worth doing.” [read more]

Source: NYP Advances

February 1, 2024

On February 23, 2024, Senior Staff Associate Danurys L. Sanchez and five other awardees were honored by Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons (VP&S) with Martha A. Hooven Awards for Excellence. These awards are given annually to recognize individuals at VP&S who make significant contributions to the medical school’s workplace and community.

This year, Danurys (Didi) and her co-awardees were chosen from more than 160 nominations. This is the second time that Didi has received a Martha A. Hooven Award for Excellence, as mentioned by Dr. Olajide Williams, professor of neurology and vice dean of community health, who presented the award [watch the ceremony, with Didi's award beginning at 10:25.] “Didi understands cultural humanity; she understands mutual respect; she understands that the dedication to health justice is the only way to achieve strong recruitment and retention from our local community,” explains Dr. Williams.

In accepting the award, Didi was quick to credit the dedication of her team and colleagues, noting that she is “surrounded every day by people who are leaving their marks in this community…we are doing so much, and my deeds out there are a testament that I’m not by myself.”

The faculty and staff of the Department of Neurology, the Taub Institute for Research on Alzheimer’s Disease and the Aging Brain, and the Gertrude H. Sergievsky Center congratulate Didi on this well-deserved honor!

Community Service AwardDanurys L. Sanchez is a senior staff associate for the Gertrude H. Sergievsky Center, where she collaborates with principal investigators to ensure the fulfillment of the center’s research mission. She has been a key team member for the Washington Heights-Inwood Columbia Aging Project since 2007, working to recruit participants, connect community members with relevant health care providers and social services, and increase community understanding of Alzheimer’s disease and related disorders. She also helps connect departments, faculty members, and researchers with community organizations, creating networks for all parties to collaborate and share resources.

February 18, 2024

By Gary Goldenberg

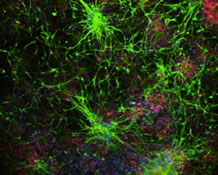

Over the years, zebrafish (and to a lesser extent killifish) have become an important experimental model in biomedical research, thanks to their genetic similarity to humans, transparent embryos, rapid development, and regenerative abilities, among other features. Columbia researchers are using these finned wonders to gain insights into human health and disease. Caghan Kizil, PhD, MSc, Associate Professor of Neurological Sciences in Neurology and in the Taub Institute, uses zebrafish in his research on Alzheimer's disease. [read more about how other Columbia researchers are using zebrafish in their work]

Can zebrafish teach us how to regenerate neurons?

No one would argue that zebrafish, whose brains are the size of a sesame seed, are smarter than humans. But these tiny aquatic animals can do a few tricks that humans cannot, such as growing scores of new brain neurons in response to neurological pathologies such as Alzheimer’s disease or injury, even well into adulthood. In contrast, once past childhood, humans can manage to regenerate only a smattering of neurons, a rate that declines even more with disease.

Using zebrafish as a model organism, Caghan Kizil, PhD, associate professor of neurological sciences (in neurology and in the Taub Institute) at the Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons, is gaining new insights into the molecular mechanisms that underlie neuronal regeneration, or neurogenesis.

“The beauty of zebrafish is that we can get human-relevant experimental results in weeks instead of months or years with other animal models,” adds Kizil. “We can even get these fish to perform memory tests to investigate the cognitive consequences of therapeutic interventions for neurological diseases.”

Thus far, Kizil’s studies have revealed a key molecule (nerve growth factor receptor) that controls nerve regeneration in zebrafish. The same molecule appears to be active in humans during early development but not in Alzheimer’s patients.

“If we could kickstart neurogenesis in humans, we might be able to slow the progression of Alzheimer’s by enhancing the brain’s resilience,” says Kizil. His team has already identified two potential targets for drug therapy. The researchers are designing compounds to selectively hit those targets, which they will evaluate in zebrafish.

Source: CUIMC Newsroom